The OG Photoshop: Portrait Painters and the Art of Retouching

As the beautiful exhibit of John Singer Sargent portraits takes off at the Tate Museum in London, Sargent & Fashion until July 7th, and the world is continually abuzz with the often hyperbolic, hypocritical judgments of whether or not photos can, should, are retouched by their creators, we take a look at the longstanding tradition of “portrait enhancing” and the innate human desire to always give our best face.

Lady Agnew of Lochnaw, née Gertrude Vernon, by John Singer Sargent, 1892

Photograph of Lady Agnew, still Gertrude Vernon, taken by John Edwards, 1889

As the world becomes more and more obsessed with photo filters, photo editing and the slick trickery of Artificial Intelligence, we feel desperately overwhelmed with the onslaught of compulsive photo manipulation, so it helps to have a bit of perspective, or at least some historical context, to ease our doomsday sensitivities. The human fascination with presenting the “best version” of ourselves or taking hold of the narrative when presenting ourselves goes back many hundreds of years. What we resoundingly agree on calling “art” has often been, at the very least, unabashed self-promotion bearing little likeness to the subject and at worst, influenced the course of history through its brazen misrepresentation of the truth.

Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul, crossing the Alps at Great St. Bernard Pass, 20 May 1800, by Jacques-Louis David, 1803

The above portrait of Emperor Napoleon, then still only First Consul of France, was painted by the French artist, Jacques-Louis David, at the turn of the 19th century, and depicts Napoleon’s crossing of the Alps into Italy in 1800, where the famed general would go on to win several important military victories, including the Battle of Marengo. But this compelling and beautifully painted portrait is actually more of a strategically crafted piece of propaganda. In actuality, Napoleon didn’t ride a horse. He rode a sturdy, much less photogenic mule; all horses on the dangerous passage were led on foot. Napoleon certainly did not wear such an impractical, sumptuous and voluptuous cape, he wore a heavy overcoat. And his stirringly confident gaze would have been more difficult for him to portray in such a stance, as he was a less-than-confident rider. And the elements whirling around him, as he comes off cool as a cucumber, powerful and secure in his capabilities, ensures no doubts exist in the viewer’s mind that his name belongs etched in rock, right above those of Hannibal (the Carthaginian general who conquered Italy) and Karolus Magnus (Charlemagne — Emperor of the Romans and King of the Franks), as the painter has done on the bottom left.

Self-portrait of Benedictine abbess and scribe, Hildegard of Bingen, painted in her autobiographical Scivias illustrated work, circa 1151-52

Humans have expressed themselves through art and painting for millennia, but portraiture, as we know it today, and not perhaps as that of the Ancient Egyptians which was meant for the Spiritual World, wasn't a truly developed practice until the late Medieval and early Renaissance era. Previously, most depictions of people in art were saved for religious works, especially those made by a specific artist or scribe or created thanks to a particular benefactor who might be allowed to be immortalized in the artwork alongside the saints and angels and if so, only in a most humble position of reverence.

Jean II le Bon, one of the earliest known portraits, dated 14th century Artist Unknown

In the period when portraits were reserved mainly for royalty and nobility, used to promote their power and reputation throughout the courts of Europe — and also their desirability as marital partners — the artist was mainly considered more of a craftsman, fulfilling the requests and desires of the patron. But as portraiture evolved and more people, particularly of the merchant classes, had access to commissioning portraits of themselves and their families, the artist himself became a distinguished and renowned figure. Those who could afford it and were allowed the prestigious opportunity, would seek out the very best, and so the painter himself became a figure. And one of the ways, these figures honed their craft was by taking selfies — or rather painting self-portraits.

King Charles I by Anthony van Dyck, 1635-36

Three of the over one hundred self-portraits Rembrandt painted over the course of his career as a painter; painted in 1628, 1640, 1657.

As portrait paintings became de rigueur for the upper classes, the masters of the “Grand Manner” in England, like Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough took inspiration from the masters of the Renaissance, implementing symbolism and classical imagery throughout their paintings. The glorious depictions of renowned figures of the time are inspiring but besides reading some journals or comments from contemporaries we can’t know for ourselves what the sitters actually looked like.

Lady Elizabeth Compton by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1780-82

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire by Thomas Gainsborough, 1783

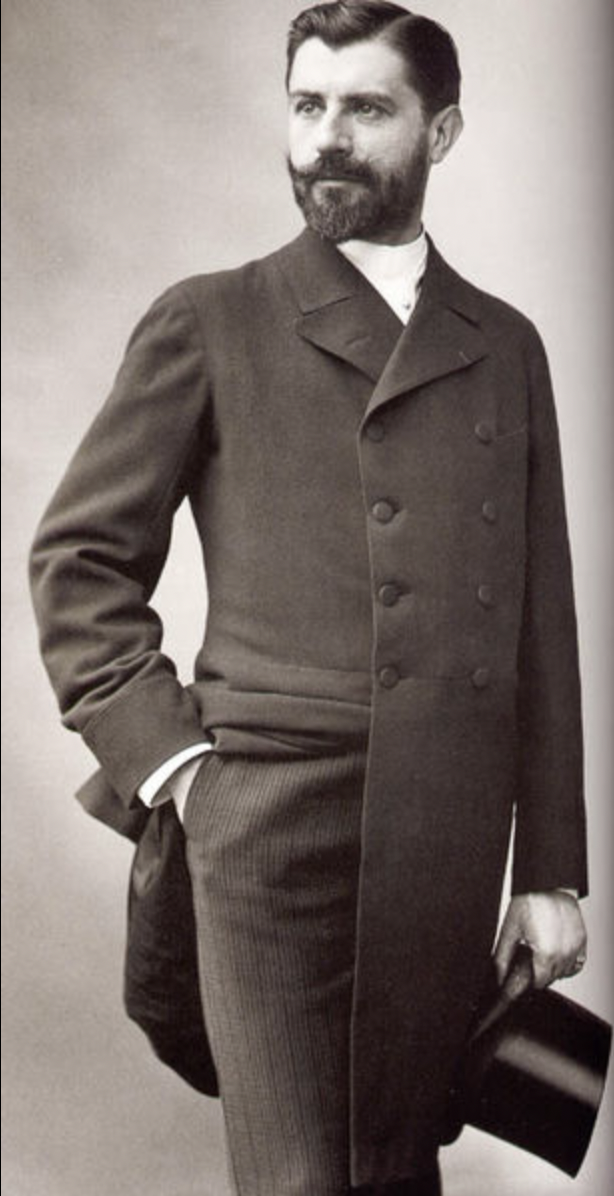

Not until the dawn of photography, which emerged in the first part of the 19th century, threatening to completely displace artist portraitists altogether, could we understand the kind of “tweaking” and embelishments that occurred with the paintbrush. Some of the most prolific and sought after portraitists which emerged in the 19th and early 20th century, such as Giovanni Boldini, John Singer Sargent and Philip de László, who continued the long-ingrained habit of making the sitter look their very best, could now have their artwork compared to the “real deal" of the daguerreotype process, though still without color. The slimmer necks, long and elegant décolletages, heightened cheekbones, widened eyes, sculpted noses and profiles and all-around much more stylized figures of the painted portraits were now contrasting with the black and white blunter versions of reality. Men of course, were subject to the same indulgences and vanities as the female sitters, and more prominent brows, broader shoulders, more refined features and more imposing stature were all part of the artistry in portraiture.

Her Royal Highness, the Duchess of York, née Lady Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon, painted by Philip de László in 1925 later known as Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother, Consort of George VI

Photograph of Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon, Duchess of York circa 1925

Photograph of Dr. Samuel Jean Pozzi, circa 1898

Portrait of Dr. Pozzi at Home by John Singer Sargent, 1881

As the popularity of photography grew and the new medium became the preference du jour for its ease of use and practicality, new ways of “photo editing” cropped up. There were even entire books dedicated to the subject of early photo editing techniques, such as The Art of Retouching Photographic Negatives (1898). The practices of scratching out unwanted amounts of waistline, shaving off parts of profiles, contouring faces, pencil corrections, and so on were so pervasive in the Victorian Era that whole articles were written about the extreme lengths people were taking to manipulate the photographs and how the results were oftentimes too absurd, the commonly accepted, yet overly snatched, 18-inch waist was one of the more controversial results.

And yet, one of the greatest “photoshop fails” of royal history was created long before the invention of the photograph. It is the portrait of Anne of Cleves by none other than Hans Holbein, who was court painter at the time for Henry VIII. Holbein was sent to Cleves to immortalize the young woman and created such a compelling depiction of Anne that the king married her without even having met her — he swiped right, so to speak — yet, upon meeting her his regret was great, perhaps not only because of her disappointing looks but also a result of their language barrier and cultural differences. They eventually married, but after only six months the king proceeded to annul the marriage. In today’s parlance, King Henry friend-zoned Anne, which might seem rude but was nowhere near as drastic as the fate of several other of King Henry’s wives. He offered her a generous settlement, land and position and the title of “King’s Sister,” which she gladly — and wisely — accepted.

Anne of Cleves by Hans Holbein

This may seem all worlds away from what we are witnessing today, almost benign, though at the time it no doubt seemed just as provoking and vanity obsessed as today’s retouching obsession. But we must realize that 20/20 hindsight should have its benefits in the present: perspective. And taking certain things with a grain of salt, or at the very least ensuring we take a more introspective approach to our own way of being before we so quickly point the finger, should perhaps be part of our evolution — technological, as well as, spiritual. The human psyche strives for perfection, because deep down that is our truest nature. It’s just that sometimes we reach for said perfection in erroneous, outward directions, but as we have seen, sometimes great works of art can come from it, all the same.